Over the course of a career that began at the time of the birth of neorealism and lasted more than 60 years, Suso Cecchi d’Amico worked on the screenplays of more than 120 films (mainly, but not exclusively, Italian) directed by both newcomers and established directors. Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023 presents a tribute to her, curated by her children, Masolino, Silvia and Caterina d’Amico. Suso Cecchi d’Amico's aim was never to impose her own ideas but to understand and support the projects and poetics of the authors with whom she worked. On the other hand, like any artist, she clearly possessed her own voice and personality, which this section proposes to trace through films that are very different in tone, genre and language. It is certainly a partial but undoubtedly fascinating selection, presenting significant works chosen from a rich and heterogeneous filmography that few other screenwriters can boast. For this post, Ivo Blom selected a series of postcards and stills of her films and wrote the text for this post for which he used an interview he had with her in 2004.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Italian postcard by Rotocalco Dagnino, Torino. Photo: Lux Film. Alida Valli as Countess Livia Serpieri and Farley Granger as Lt. Franz Mahler in Luchino Visconti's historical film Senso (1954).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

German postcard. Photo Ufa. Sophia Loren in La fortuna di essere donna/What a Woman! (Alessandro Blasetti, 1956).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Publicity still used in Germany, distributed by Rank, the mark of the German censor FSK. Thomas Milian andRomy Schneider in Luchino Visconti's episode Il Lavoro in the episode film Boccaccio 70 (1962).

Suso Cecchi D’Amico, pseudonym of Giovanna Cecchi D'Amico, was born in Rome in 1914 to Tuscan parents: the writer Emilio Cecchi (from whom she took her birth name Cecchi) and the painter Leonetta Pieraccini. After finishing the Lycée Chateaubriand in Rome, she did not enrol at university, as she had not taken a diploma in Latin and Greek. 'To continue my studies I could only enrol in one or two faculties, such as botany, which frankly did not interest me'. After a stay abroad, in Switzerland and England, she decided to get a job. Thanks to the intervention of Minister Giuseppe Bottai, "the only hierarch who had any relationship with intellectuals", she was hired at the Ministry of Corporations, later the Ministry of Trade and Currency, where she worked for almost seven years as personal secretary to Eugenio Anzilotti, Director General of Foreign Trade.

In 1938 she married musicologist Fedele D'Amico, Silvio's son, by whom she had three children: Masolino, Silvia and Caterina, who all later on would have important careers in Italian culture. Alone or together with her father, she performed many translations from English and French, including Thomas Hardy's 'Jude the Obscure', 'Tobacco Road', 'Life with Father', 'Look Homeward, Angel', William Shakespeare’s 'The Merry Wives of Windsor' and 'Othello'. She abandoned this activity, in which she did not show the facility that her son Masolino would have when he began working for the cinema.

During the Second World War, while her husband, a member of the communist Catholics with Adriano Ossicini and Franco Rodano, led a clandestine life in Rome and directed the newspaper Voce Operaia, she moved for six to seven months to Poggibonsi, to the villa of her uncle Gaetano Pieraccini, a doctor and politician who would be the first mayor of Florence after the Liberation. At the end of the conflict, while her husband was hospitalised in Switzerland to recover from tuberculosis, she was "forced to scramble every which way to support herself, her first two children [...] and the house, populated by nannies and other women". Among the curious occupations of this period, she gave lessons in good manners to Maria Michi and English conversation to Giovanna Galletti, both of whom were actresses in Roberto Rossellini’s Roma città aperta/Rome Open City (1945).

Suso Cecchi D’Amico worked on her first screenplay, Avatar, a romantic story set in Venice, inspired by a story by Théophile Gautier, with Ennio Flaiano, Renato Castellani and Alberto Moravia, for Carlo Ponti, then not yet a major producer. But the project was abandoned before even arriving at a proper screenplay, Castellani alone completing a treatment. Together with Castellani, she worked on a story based on a subject by playwright Aldo De Benedetti,Mio figlio professore (1946), directed by Castellani himself and starring Aldo Fabrizi and the Nava sisters. Together with Piero Tellini, she wrote Vivere in pace (1947) and L'onorevole Angelina (1947), both directed by Luigi Zampa and starring Aldo Fabrizi and Anna Magnani respectively, with whom she began to associate assiduously, forging one of her rare friendships with actors. For the subject of Vivere in pace, also signed by Tellini and Zampa but essentially her own, she won the Nastro d'argento for the best subject.

Suso Cecchi participated with Federico Fellini, although almost always absent from meetings, in the screenplay for the film Il delitto di Giovanni Episcopo (1947), based on a novel by Gabriele D'Annunzio and directed by Alberto Lattuada. She wrote with Ennio Flaiano the screenplay for Roma città libera (1947), by Marcello Pagliero, based on La notte porta consiglio, a subject by Flaiano himself. The screenplay sessions with Flaiano passed 'between chats, criticisms and digressions on the subject. There was matter to be extracted to season ten films, and all would have been lost if it had been up to him to extract the juice'. She wrote the screenplays of Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (1948) with Cesare Zavattini, proposing the finale with the attempted bicycle theft, of Le Mura di Malapaga (1949), directed by René Clément and Oscar winner for best foreign work, and also collaborated on the screenplay of De Sica’s Miracolo a Milano (1951). Her professional association with Zavattini was interrupted when he disowned the film È più facile che un cammello... directed by Zampa, for which he wrote the subject, while Cecchi D'Amico and Vitaliano Brancati edited the screenplay.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Aldo Fabrizi and Gar Moore in Vivere in pace (1947)]()

Italian postcard by Ed. Gel. Aldo Fabrizi and Gar Moore in Vivere in pace (Luigi Zampa, 1947).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Aldo Fabrizi in Il delitto di Giovanni Episcopo]()

Italian postcard by Ed. Gel, series Aldo Fabrizi. Poster/lobby card for Il delitto di Giovanni Episcopo/Flesh Will Surrender (Alberto Lattuada, 1947), based on the novel by D'Annunzio.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Ladri di biciclette (1948)]()

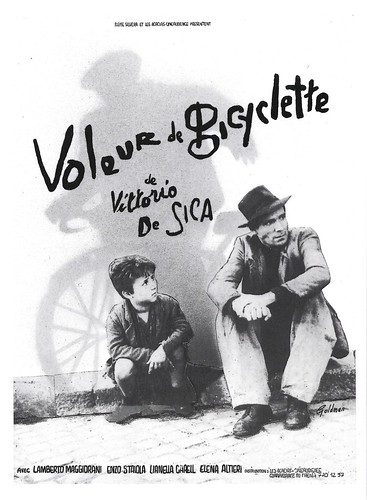

Postcard, reproduction of a French poster based on a classic still from Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948), with Lamberto Maggiorani and Enzo Staiola.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Miracolo a Milano (1951)]()

Postcard, reproduction of Italian poster for Miracolo a Milano (Vittorio De Sica, 1951). Poster design by Ercole Brini for ENIC. Hardly recognisable are the leading actors Irma Gramatica, Francesco Golisano and Brunella Bovo.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Anna Maria Ferrero and Sandro Milani in Febbre di vivere (1953)]()

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano (Milan), no. 466. Photo: Anna Maria Ferreroand Sandro Milani in Febbre di vivere/Eager to live (Claudio Gora, 1953).

Suso Cecchi D’Amico worked with Mario Monicelli and the couple Age & Scarpelli on the writing of I soliti ignoti/Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958). Screenplay meetings often ended with arguments between Age and Scarpelli, which Monicelli and Cecchi D'Amico kept out of, so as not to give them importance. Uncredited she participated in the script of Alessandro Blasetti’s Fabiola (1940), and while credited she co-wrote the script for William Wyler’s Roman Holiday (1953). With Ennio Flaiano, she wrote the screenplays for the adorable comedies Peccato che sia una canaglia (1955), forcing Sophia Loren into the lead role, after seeing her in Cinecittà, "Beautiful, excessive, decorative as a Christmas Tree" as Cecchi said herself, and La fortuna di essere donna (1956), again starring Loren.

From ca. 1950, Suso Cecchi D’Amico became the regular (co-)screenwriter of Luchino Visconti. The first screenplay for Visconti was La carrozza del Santissimo Sacramento, which was not made because the producer feared the anticlerical stance in the film script, so the project passed to Jean Renoir. Then it was the turn of Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951), with Anna Magnani and Walter Chiari. The latter plays a major character who, barely hinted at in the first version of the screenplay, was later developed for reasons related to the film's distribution. Afterwards, she co-wrote the script of Visconti’s episode Anna of ‘the portmanteau film Siamo donne (1953). The screenplay for Visconti’s Senso (Luchino Visconti, 1954), based on a novella by Camillo Boito, was not entirely shot. D'Amico recounts: "I did not yet have much filming experience with Luchino and I did not foresee all the delays in the villa scenes, all the crossing of rooms to fetch something. At a certain point in the shoot, producer Gualino called me and asked me to tell Visconti that he was going to close. There was more footage than the length of the film and the budget had been greatly exceeded. So the scenes of Alida Valli crossing the battlefields in a carriage were never shot. The Countess Serpieri's journey is reduced to an apparition of the woman in the carriage that was supposed to pass through the bloody troops.” Also, the final scenes were shot in Rome instead, in Trastevere and in a ditch of Castel Sant-Angelo.

In 1957 Suso Cecchi with Visconti, producer Cristaldi and others raised a cooperative to make Le notti bianche (Luchino Visconti, 1957). Suso Cecchi collaborated with Vasco Pratolini on the subject of Visconti’s Rocco e i suoi fratelli/Rocco and His Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960). She wrote the screenplay with Pasquale Festa Campanile and Massimo Franciosa, both of whom, coming from the south of Italy, proved very useful for the psychology of the characters and the tone of the dialogues. In the screenplay for Il Gattopardo/The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963), at Visconti's suggestion, she cut the entire final part of Tomasi di Lampedusa's novel to give in the ball scene the sense of the Prince's death and the collapse of the Gattopardi's aristocratic society. For the screenplay of the film Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa.../Sandra (Luchino Visconti, 1965), she took her cue from the tragedy of 'Electra'. For the film Lo straniero/The Stranger (Luchino Visconti, 1967) she was obliged to faithfully transpose Camus' book. Before the editing phase of the film Ludwig (Luchino Visconti, 1973), she was with Visconti when the director suffered a stroke that half paralyzed him, and from which he only recovered with great difficulty. Suso Cecchi also worked on the scripts of Gruppo di famiglia in un interno/Conversation Piece (Luchino Visconti, 1974) and L'innocente/The Innocent (Luchino Visconti, 1976).

As for the development of Senso (Luchino Visconti, 1954), Visconti and Suso had worked beforehand on a screenplay called Marcia nuziale. It was a script with many characters, which the state censors banned because it was about a divorce. There were demonstrations for divorces at the time and the censors did not want to get involved. Gualino instructed Visconti and Suso to come up with a new suggestion within days. Thus Boito's novella rolled out. Concerning the change of characters in the film, not only the introduction of Camillo Ussoni's character but also Franz's character changing from a bonehead to a devilish seducer, Suso remarked: “That had partly to do with the actors we wanted. Originally, Visconti wanted Marlon Brando and not Farley Granger but the producer, in view of foreign exports, wanted Granger, even though he was not at all well known in Italy at the time.

A notable change in production happened after the death of the director of photography, Aldo (Aldo Graziati alias G.R. Aldò). Visconti was used to discussing every shot at length with Aldo, who was a creative genius. They both enjoyed it and learned from each other. Robert Krasker replaced Aldo after his death in a car crash. Krasker was a highly respected cameraman, who had done the colour film Henry Vwith Laurence Olivier. Krasker asked Visconti why the shoot had to be discussed so extensively beforehand, and from then on, there was no discussion of the shoots at all, much to Visconti's disappointment.” When asked about the reason for changing the title of Boito's Senso to Uragano d'estate and eventually back to Senso, Suso responded: “We had a whole page of titles at one point, not just Uragano d'estate. We spent a whole day making up titles. There was little reasoning for that, the only thing was that sometimes in films people protested like in Rocco because their name was used and they were the only ones with that name (in Rocco, Pafundi became Parondi). In Senso, the Count is first called Pietromarchi, then Serpieri, and Franz Mahler was originally called Hans Weil”. (Interview by Ivo Blom with Suso Cecchi D’Amico, 11 May 2004.)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Fabiola (1949)]()

Postcard, reproduction. Danish poster by Atlantic Film for the film Fabiola (Alessandro Blasetti, 1949), starring Michèle Morgan and Henri Vidal.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Anna Magnani in Bellissima]()

Reproduction of press photo. Photo by Paul Ronald. Anna Magnaniin Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951). Collection Ivo Blom, ex-collection Egbert Barten.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday (1953)]()

Dutch postcard by Takken / 't Sticht, Utrecht, no. 1469. Photo: Paramount. Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Farley Granger in Senso (1954)]()

Italian postcard by Bromostampa, Milano, no. 7. Photo: Farley Granger in Senso (1954).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![I soliti ignoti (1958)]()

Italian postcard by Coop. soc. Archivio immagini cinema. Card made for exhibition on Marcello Mastroianni. Vittorio Gassman, Marcello Mastroianni and Carlo Pisacane in I soliti ignoti/Big Deal on Madonna Street (Mario Monicelli, 1958).

Il Gattopardo/The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963) officially employed five screenwriters: Luchino Visconti, Suso Cecchi D’Amico, Enrico Medioli (who was just starting out at the time and was a protege of Suso and Visconti) and two men added on behalf of the Titanus production company, Massimo Franciosa and Pasquale Festa Campanile. The latter two had also collaborated on Rocco and His Brothers, with each writer writing one act. Suso Cecchi D’Amico said in an interview with Ivo Blom in 2004: “At first, Visconti was sour about the imposed addition of Franciosa and Festa Campanile, but the two turned out to be intelligent and sympathetic and Visconti thawed. In the end, everyone wrote one part, Visconti part one: The ‘Rosario’, I did part two: the villeggiatura, and the war scenes (then still in the middle of the villeggiatura scene), Festa Campanile part three: the plebiscite, Medioli part four: the attics and the meeting with Chevalley, and Franciosa part five: the ball."

This did not mean that you still recognise the signature of each individual writer in the film. Each written part was talked through and edited with the whole group. The screenplay had a huge number of versions and expanded so much, because the authors wanted to explain so much about Italian history, especially for the international market, that the screenplay became endlessly long. Suso Cecchi D’Amico: "At some point, it was decided: back to the novel and if people abroad don't understand everything, so be it. Huge scenes were either cut out or condensed, which is a common process. You first grow to absurd proportions and then you cut back."

It was not just because of length that scenes were cut out. Suso Cecchi D’Amico: "The cut of the scene of the fusillade at the end was a deliberate choice by Visconti, to prevent that scene from becoming the climax of the film, rather than the Proustian ball with its slowing down of time and its image of decline of don Fabrizio and of his class. It would become too explanatory. Of Salina's daughters, there is now only one, Concetta, who has real form and dialogue; the others have become sort of extras. This was a conscious choice; you can't give too many people body and it has to do with identification with the audience. Incidentally, many characters in the film were based on characters from the screenwriters' environment; character traits were borrowed from contemporary acquaintances.” (Interview by Ivo Blom with Suso Cecchi D’Amico, 11 May 2004.)

With Michelangelo Antonioni, Suso Cecchi made I vinti (1952), inspired by news events, carrying out investigations and collecting material found in the press and court documents, La signora senza camelie (1953) and Le amiche (1955), winner of the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. She collaborated on the screenplay for the film Camicie rosse (Anita Garibaldi) (1952), directed by Francesco Rosi and Goffredo Alessandrini, starring Anna Magnani, but the film was defined by Cecchi d'Amico as a "senseless adventure". With Francesco Rosi she worked on three other films: La sfida (1957), I magliari (1959) and Salvatore Giuliano (1962). With Luigi Comencini she worked on the films Proibito rubare (1948), La finestra sul Luna Park (1956), Le avventure di Pinocchio (1972), written for television, Cuore (1984) and Infanzia, vocazione e primi esperienze di Giacomo Casanova, veneziano (1969). In her later life, Suso Cecchi often collaborated with her good friend Mario Monicelli, with whom she worked for the first time on Proibito (1954), followed by I soliti ignoti (1958), Risate di gioia (1960), and 14 other films, the last time for Le rose del deserto (2010). Other memorable films on which she co-wrote were Cielo sulla palude (Augusto Genina, 1949), Prima comunione (Blasetti, 1950), Il mondo le condanna (Gianni Franciolini, 1953), Nella città l'inferno (Renato Castellani, 1959), Estate violenta (Valerio Zurlini, 1959), Gli indifferenti (Francesco Maselli, 1964), Metello (Mauro Bolognini, 1970), etc.

Suso Cecchi d’Amico shared several Italian awards with her co-writers for various films and was co-nominated for an Oscar for best screenplay for Mario Monicelli’s Casanova 70, in 1980 she received lifetime career David di Donatello. In 1988, the University of Bari awarded her an honorary degree in Foreign Languages and Literature with the following motivation: “Her fierce technique and vast culture were invaluable in the literary work of film ... She reworked the original subjects with profound literary insight and extraordinary cinematographic sense". In 1994 the Venice Film Festival awarded her the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. Since 2012, the city of Rosignano Marittimo awards the Premio Suso Cecchi D'Amico Castiglioncello per la sceneggiatura, for the best original screenplay for an Italian film.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Claudia Cardinale, Alain Delon, Max Cartier and Renato Salvatori in Rocco e i suoi fratelli (1960)]()

Small Czech collectors card by Pressfoto, Praha (Prague), 1965, no. S 101/5. Photo: Claudia Cardinale, Alain Delon, Max Cartier and Renato Salvatori in Rocco e i suoi fratelli/Rocco and His Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Alain Delon, Claudia Cardinale and Burt Lancaster in Il Gattopardo (1963)]()

Czech postcard by UPTF / Pressfoto, Praha (Prague), no. C 198, 1965. Photo: G.B. Poletto. Alain Delon, Claudia Cardinale and Burt Lancaster in Il Gattopardo/The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa (1965)]()

Vintage press photo. Publicity still for Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa/ Sandra (Luchino Visconti, 1965), depicting Michael Craig, Claudia Cardinale and Jean Sorel. Photo by Mario Tursi. Collection: Ivo Blom, ex-collection Egbert Barten.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Helmut Berger and Romy Schneider in Ludwig (1972)]()

French postcard in the Collection Cinéma by Editions Art & Scene, Paris, no. CI 16, 1996. Photo: Mario Tursi. Helmut Berger and Romy Schneider in Ludwig (Luchino Visconti, 1972).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Giancarlo Giannini in L'Innocente (1976)]()

Italian press photo. Photo: Mario Tursi. Giancarlo Giannini in L'Innocente/The Innocent (Luchino Visconti, 1976). Collection: Ivo Blom.

Sources: Wikipedia (Italian, French and English), IMDb, and an unpublished interview by Ivo Blom with Suso Cecchi D’Amico, 11 May 2004.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Italian postcard by Rotocalco Dagnino, Torino. Photo: Lux Film. Alida Valli as Countess Livia Serpieri and Farley Granger as Lt. Franz Mahler in Luchino Visconti's historical film Senso (1954).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

German postcard. Photo Ufa. Sophia Loren in La fortuna di essere donna/What a Woman! (Alessandro Blasetti, 1956).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Publicity still used in Germany, distributed by Rank, the mark of the German censor FSK. Thomas Milian andRomy Schneider in Luchino Visconti's episode Il Lavoro in the episode film Boccaccio 70 (1962).

First screenplay

Suso Cecchi D’Amico, pseudonym of Giovanna Cecchi D'Amico, was born in Rome in 1914 to Tuscan parents: the writer Emilio Cecchi (from whom she took her birth name Cecchi) and the painter Leonetta Pieraccini. After finishing the Lycée Chateaubriand in Rome, she did not enrol at university, as she had not taken a diploma in Latin and Greek. 'To continue my studies I could only enrol in one or two faculties, such as botany, which frankly did not interest me'. After a stay abroad, in Switzerland and England, she decided to get a job. Thanks to the intervention of Minister Giuseppe Bottai, "the only hierarch who had any relationship with intellectuals", she was hired at the Ministry of Corporations, later the Ministry of Trade and Currency, where she worked for almost seven years as personal secretary to Eugenio Anzilotti, Director General of Foreign Trade.

In 1938 she married musicologist Fedele D'Amico, Silvio's son, by whom she had three children: Masolino, Silvia and Caterina, who all later on would have important careers in Italian culture. Alone or together with her father, she performed many translations from English and French, including Thomas Hardy's 'Jude the Obscure', 'Tobacco Road', 'Life with Father', 'Look Homeward, Angel', William Shakespeare’s 'The Merry Wives of Windsor' and 'Othello'. She abandoned this activity, in which she did not show the facility that her son Masolino would have when he began working for the cinema.

During the Second World War, while her husband, a member of the communist Catholics with Adriano Ossicini and Franco Rodano, led a clandestine life in Rome and directed the newspaper Voce Operaia, she moved for six to seven months to Poggibonsi, to the villa of her uncle Gaetano Pieraccini, a doctor and politician who would be the first mayor of Florence after the Liberation. At the end of the conflict, while her husband was hospitalised in Switzerland to recover from tuberculosis, she was "forced to scramble every which way to support herself, her first two children [...] and the house, populated by nannies and other women". Among the curious occupations of this period, she gave lessons in good manners to Maria Michi and English conversation to Giovanna Galletti, both of whom were actresses in Roberto Rossellini’s Roma città aperta/Rome Open City (1945).

Suso Cecchi D’Amico worked on her first screenplay, Avatar, a romantic story set in Venice, inspired by a story by Théophile Gautier, with Ennio Flaiano, Renato Castellani and Alberto Moravia, for Carlo Ponti, then not yet a major producer. But the project was abandoned before even arriving at a proper screenplay, Castellani alone completing a treatment. Together with Castellani, she worked on a story based on a subject by playwright Aldo De Benedetti,Mio figlio professore (1946), directed by Castellani himself and starring Aldo Fabrizi and the Nava sisters. Together with Piero Tellini, she wrote Vivere in pace (1947) and L'onorevole Angelina (1947), both directed by Luigi Zampa and starring Aldo Fabrizi and Anna Magnani respectively, with whom she began to associate assiduously, forging one of her rare friendships with actors. For the subject of Vivere in pace, also signed by Tellini and Zampa but essentially her own, she won the Nastro d'argento for the best subject.

Suso Cecchi participated with Federico Fellini, although almost always absent from meetings, in the screenplay for the film Il delitto di Giovanni Episcopo (1947), based on a novel by Gabriele D'Annunzio and directed by Alberto Lattuada. She wrote with Ennio Flaiano the screenplay for Roma città libera (1947), by Marcello Pagliero, based on La notte porta consiglio, a subject by Flaiano himself. The screenplay sessions with Flaiano passed 'between chats, criticisms and digressions on the subject. There was matter to be extracted to season ten films, and all would have been lost if it had been up to him to extract the juice'. She wrote the screenplays of Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (1948) with Cesare Zavattini, proposing the finale with the attempted bicycle theft, of Le Mura di Malapaga (1949), directed by René Clément and Oscar winner for best foreign work, and also collaborated on the screenplay of De Sica’s Miracolo a Milano (1951). Her professional association with Zavattini was interrupted when he disowned the film È più facile che un cammello... directed by Zampa, for which he wrote the subject, while Cecchi D'Amico and Vitaliano Brancati edited the screenplay.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Italian postcard by Ed. Gel. Aldo Fabrizi and Gar Moore in Vivere in pace (Luigi Zampa, 1947).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Italian postcard by Ed. Gel, series Aldo Fabrizi. Poster/lobby card for Il delitto di Giovanni Episcopo/Flesh Will Surrender (Alberto Lattuada, 1947), based on the novel by D'Annunzio.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Postcard, reproduction of a French poster based on a classic still from Ladri di biciclette/Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948), with Lamberto Maggiorani and Enzo Staiola.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Postcard, reproduction of Italian poster for Miracolo a Milano (Vittorio De Sica, 1951). Poster design by Ercole Brini for ENIC. Hardly recognisable are the leading actors Irma Gramatica, Francesco Golisano and Brunella Bovo.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Italian postcard by Bromofoto, Milano (Milan), no. 466. Photo: Anna Maria Ferreroand Sandro Milani in Febbre di vivere/Eager to live (Claudio Gora, 1953).

Monicelli and Visconti

Suso Cecchi D’Amico worked with Mario Monicelli and the couple Age & Scarpelli on the writing of I soliti ignoti/Big Deal on Madonna Street (1958). Screenplay meetings often ended with arguments between Age and Scarpelli, which Monicelli and Cecchi D'Amico kept out of, so as not to give them importance. Uncredited she participated in the script of Alessandro Blasetti’s Fabiola (1940), and while credited she co-wrote the script for William Wyler’s Roman Holiday (1953). With Ennio Flaiano, she wrote the screenplays for the adorable comedies Peccato che sia una canaglia (1955), forcing Sophia Loren into the lead role, after seeing her in Cinecittà, "Beautiful, excessive, decorative as a Christmas Tree" as Cecchi said herself, and La fortuna di essere donna (1956), again starring Loren.

From ca. 1950, Suso Cecchi D’Amico became the regular (co-)screenwriter of Luchino Visconti. The first screenplay for Visconti was La carrozza del Santissimo Sacramento, which was not made because the producer feared the anticlerical stance in the film script, so the project passed to Jean Renoir. Then it was the turn of Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951), with Anna Magnani and Walter Chiari. The latter plays a major character who, barely hinted at in the first version of the screenplay, was later developed for reasons related to the film's distribution. Afterwards, she co-wrote the script of Visconti’s episode Anna of ‘the portmanteau film Siamo donne (1953). The screenplay for Visconti’s Senso (Luchino Visconti, 1954), based on a novella by Camillo Boito, was not entirely shot. D'Amico recounts: "I did not yet have much filming experience with Luchino and I did not foresee all the delays in the villa scenes, all the crossing of rooms to fetch something. At a certain point in the shoot, producer Gualino called me and asked me to tell Visconti that he was going to close. There was more footage than the length of the film and the budget had been greatly exceeded. So the scenes of Alida Valli crossing the battlefields in a carriage were never shot. The Countess Serpieri's journey is reduced to an apparition of the woman in the carriage that was supposed to pass through the bloody troops.” Also, the final scenes were shot in Rome instead, in Trastevere and in a ditch of Castel Sant-Angelo.

In 1957 Suso Cecchi with Visconti, producer Cristaldi and others raised a cooperative to make Le notti bianche (Luchino Visconti, 1957). Suso Cecchi collaborated with Vasco Pratolini on the subject of Visconti’s Rocco e i suoi fratelli/Rocco and His Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960). She wrote the screenplay with Pasquale Festa Campanile and Massimo Franciosa, both of whom, coming from the south of Italy, proved very useful for the psychology of the characters and the tone of the dialogues. In the screenplay for Il Gattopardo/The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963), at Visconti's suggestion, she cut the entire final part of Tomasi di Lampedusa's novel to give in the ball scene the sense of the Prince's death and the collapse of the Gattopardi's aristocratic society. For the screenplay of the film Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa.../Sandra (Luchino Visconti, 1965), she took her cue from the tragedy of 'Electra'. For the film Lo straniero/The Stranger (Luchino Visconti, 1967) she was obliged to faithfully transpose Camus' book. Before the editing phase of the film Ludwig (Luchino Visconti, 1973), she was with Visconti when the director suffered a stroke that half paralyzed him, and from which he only recovered with great difficulty. Suso Cecchi also worked on the scripts of Gruppo di famiglia in un interno/Conversation Piece (Luchino Visconti, 1974) and L'innocente/The Innocent (Luchino Visconti, 1976).

As for the development of Senso (Luchino Visconti, 1954), Visconti and Suso had worked beforehand on a screenplay called Marcia nuziale. It was a script with many characters, which the state censors banned because it was about a divorce. There were demonstrations for divorces at the time and the censors did not want to get involved. Gualino instructed Visconti and Suso to come up with a new suggestion within days. Thus Boito's novella rolled out. Concerning the change of characters in the film, not only the introduction of Camillo Ussoni's character but also Franz's character changing from a bonehead to a devilish seducer, Suso remarked: “That had partly to do with the actors we wanted. Originally, Visconti wanted Marlon Brando and not Farley Granger but the producer, in view of foreign exports, wanted Granger, even though he was not at all well known in Italy at the time.

A notable change in production happened after the death of the director of photography, Aldo (Aldo Graziati alias G.R. Aldò). Visconti was used to discussing every shot at length with Aldo, who was a creative genius. They both enjoyed it and learned from each other. Robert Krasker replaced Aldo after his death in a car crash. Krasker was a highly respected cameraman, who had done the colour film Henry Vwith Laurence Olivier. Krasker asked Visconti why the shoot had to be discussed so extensively beforehand, and from then on, there was no discussion of the shoots at all, much to Visconti's disappointment.” When asked about the reason for changing the title of Boito's Senso to Uragano d'estate and eventually back to Senso, Suso responded: “We had a whole page of titles at one point, not just Uragano d'estate. We spent a whole day making up titles. There was little reasoning for that, the only thing was that sometimes in films people protested like in Rocco because their name was used and they were the only ones with that name (in Rocco, Pafundi became Parondi). In Senso, the Count is first called Pietromarchi, then Serpieri, and Franz Mahler was originally called Hans Weil”. (Interview by Ivo Blom with Suso Cecchi D’Amico, 11 May 2004.)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Postcard, reproduction. Danish poster by Atlantic Film for the film Fabiola (Alessandro Blasetti, 1949), starring Michèle Morgan and Henri Vidal.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Reproduction of press photo. Photo by Paul Ronald. Anna Magnaniin Bellissima (Luchino Visconti, 1951). Collection Ivo Blom, ex-collection Egbert Barten.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Dutch postcard by Takken / 't Sticht, Utrecht, no. 1469. Photo: Paramount. Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday (William Wyler, 1953).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Italian postcard by Bromostampa, Milano, no. 7. Photo: Farley Granger in Senso (1954).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Italian postcard by Coop. soc. Archivio immagini cinema. Card made for exhibition on Marcello Mastroianni. Vittorio Gassman, Marcello Mastroianni and Carlo Pisacane in I soliti ignoti/Big Deal on Madonna Street (Mario Monicelli, 1958).

Visconti, Antonioni, Rosi and Monicelli

Il Gattopardo/The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963) officially employed five screenwriters: Luchino Visconti, Suso Cecchi D’Amico, Enrico Medioli (who was just starting out at the time and was a protege of Suso and Visconti) and two men added on behalf of the Titanus production company, Massimo Franciosa and Pasquale Festa Campanile. The latter two had also collaborated on Rocco and His Brothers, with each writer writing one act. Suso Cecchi D’Amico said in an interview with Ivo Blom in 2004: “At first, Visconti was sour about the imposed addition of Franciosa and Festa Campanile, but the two turned out to be intelligent and sympathetic and Visconti thawed. In the end, everyone wrote one part, Visconti part one: The ‘Rosario’, I did part two: the villeggiatura, and the war scenes (then still in the middle of the villeggiatura scene), Festa Campanile part three: the plebiscite, Medioli part four: the attics and the meeting with Chevalley, and Franciosa part five: the ball."

This did not mean that you still recognise the signature of each individual writer in the film. Each written part was talked through and edited with the whole group. The screenplay had a huge number of versions and expanded so much, because the authors wanted to explain so much about Italian history, especially for the international market, that the screenplay became endlessly long. Suso Cecchi D’Amico: "At some point, it was decided: back to the novel and if people abroad don't understand everything, so be it. Huge scenes were either cut out or condensed, which is a common process. You first grow to absurd proportions and then you cut back."

It was not just because of length that scenes were cut out. Suso Cecchi D’Amico: "The cut of the scene of the fusillade at the end was a deliberate choice by Visconti, to prevent that scene from becoming the climax of the film, rather than the Proustian ball with its slowing down of time and its image of decline of don Fabrizio and of his class. It would become too explanatory. Of Salina's daughters, there is now only one, Concetta, who has real form and dialogue; the others have become sort of extras. This was a conscious choice; you can't give too many people body and it has to do with identification with the audience. Incidentally, many characters in the film were based on characters from the screenwriters' environment; character traits were borrowed from contemporary acquaintances.” (Interview by Ivo Blom with Suso Cecchi D’Amico, 11 May 2004.)

With Michelangelo Antonioni, Suso Cecchi made I vinti (1952), inspired by news events, carrying out investigations and collecting material found in the press and court documents, La signora senza camelie (1953) and Le amiche (1955), winner of the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. She collaborated on the screenplay for the film Camicie rosse (Anita Garibaldi) (1952), directed by Francesco Rosi and Goffredo Alessandrini, starring Anna Magnani, but the film was defined by Cecchi d'Amico as a "senseless adventure". With Francesco Rosi she worked on three other films: La sfida (1957), I magliari (1959) and Salvatore Giuliano (1962). With Luigi Comencini she worked on the films Proibito rubare (1948), La finestra sul Luna Park (1956), Le avventure di Pinocchio (1972), written for television, Cuore (1984) and Infanzia, vocazione e primi esperienze di Giacomo Casanova, veneziano (1969). In her later life, Suso Cecchi often collaborated with her good friend Mario Monicelli, with whom she worked for the first time on Proibito (1954), followed by I soliti ignoti (1958), Risate di gioia (1960), and 14 other films, the last time for Le rose del deserto (2010). Other memorable films on which she co-wrote were Cielo sulla palude (Augusto Genina, 1949), Prima comunione (Blasetti, 1950), Il mondo le condanna (Gianni Franciolini, 1953), Nella città l'inferno (Renato Castellani, 1959), Estate violenta (Valerio Zurlini, 1959), Gli indifferenti (Francesco Maselli, 1964), Metello (Mauro Bolognini, 1970), etc.

Suso Cecchi d’Amico shared several Italian awards with her co-writers for various films and was co-nominated for an Oscar for best screenplay for Mario Monicelli’s Casanova 70, in 1980 she received lifetime career David di Donatello. In 1988, the University of Bari awarded her an honorary degree in Foreign Languages and Literature with the following motivation: “Her fierce technique and vast culture were invaluable in the literary work of film ... She reworked the original subjects with profound literary insight and extraordinary cinematographic sense". In 1994 the Venice Film Festival awarded her the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement. Since 2012, the city of Rosignano Marittimo awards the Premio Suso Cecchi D'Amico Castiglioncello per la sceneggiatura, for the best original screenplay for an Italian film.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Small Czech collectors card by Pressfoto, Praha (Prague), 1965, no. S 101/5. Photo: Claudia Cardinale, Alain Delon, Max Cartier and Renato Salvatori in Rocco e i suoi fratelli/Rocco and His Brothers (Luchino Visconti, 1960).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Czech postcard by UPTF / Pressfoto, Praha (Prague), no. C 198, 1965. Photo: G.B. Poletto. Alain Delon, Claudia Cardinale and Burt Lancaster in Il Gattopardo/The Leopard (Luchino Visconti, 1963).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Vintage press photo. Publicity still for Vaghe stelle dell'Orsa/ Sandra (Luchino Visconti, 1965), depicting Michael Craig, Claudia Cardinale and Jean Sorel. Photo by Mario Tursi. Collection: Ivo Blom, ex-collection Egbert Barten.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

French postcard in the Collection Cinéma by Editions Art & Scene, Paris, no. CI 16, 1996. Photo: Mario Tursi. Helmut Berger and Romy Schneider in Ludwig (Luchino Visconti, 1972).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Italian press photo. Photo: Mario Tursi. Giancarlo Giannini in L'Innocente/The Innocent (Luchino Visconti, 1976). Collection: Ivo Blom.

Sources: Wikipedia (Italian, French and English), IMDb, and an unpublished interview by Ivo Blom with Suso Cecchi D’Amico, 11 May 2004.