In 1903 Méliès was at the peak of his art, creating wonderful gems such as Le Royaume des fées, a film destined to be the centrepiece of a programme at Il Cinema Ritrovato 2023, curated by Mariann Lewinsky and Karl Wratschko, made up of several genres, always with its fair share of short comedies and visual tricks. While British pioneers were contributing to the cinema with their innovative spirit, in the US – see Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery– violence and plot-driven films were already happening.

In the same year, Pathé Frères ambitiously rivalled the grand féeries with spectacular productions by Lucien Nonguet about historical figures (Napoléon, Marie Antoinette). Several Pathé titles – part of the Corricks (itinerant showmen) collection – will be presented in restored versions originating from gorgeously hand-coloured prints found in Australia. For this post, Ivo Blom selected postcards of several Pathé films from 1903.

![Don Quichotte (Pathé 1903)]()

French postcard by Alterocca, Terni, Italy. Photo: Pathé Frères. Publicity still for Don Quichotte (Ferdinand Zecca, Lucien Nonguet, 1903). Sets were by Vincent Lorant-Heilbronn. Caption: Receiving the thanks of the liberated convicts. This scene lacks in the remaining print of the film. The 1903 version is the oldest film version of Cervantes' classic tale. It is unclear who the actors were. The writing on the card is in Slovenian and says: To the better healed at home, we extend our warmest regards to you.

Don Quichotte, fully titled Aventures de Don Quichotte de la Manche, was a film in 15 tableaux, measuring some 430 meters. A reduced version of 255 m. was also launched in 1903, possibly for exhibitors who thought a film of more than 15 minutes was too long for their audience. Pathé claimed in their catalogue that all the important scenes had been kept and the entire film had kept its original character.

![Vie de Christ (1903)]()

Franco-German postcard by PH, no. 6601. Photo: Film Pathé. This may be a scene from the 1903 film La Vie et la Passion de Jésus-Christ, started in 1902 by Ferdinand Zecca and finished in 1903 by Lucien Nonguet, when Zecca moved over to Gaumont. Caption: Vie de Christ, ep. 'Die Verkündigung' (the Annunciation).

![La vie du Christ]()

French postcard. Photo: Pathé Frères. Scene from the early Pathé film La vie du Christ which might be La Vie et la passion de Jésus-Christ (Lucien Nonguet, Ferdinand Zecca, 1903). Caption: Jesus chases the merchants from the Temple. This image deviates from the one in the existing prints of Vie et passion de notre seigneur Jésus-Christ (Ferdinand Zecca, 1907).

![La vie du Christ]()

French postcard. Photo: Pathé Frères. Scene from the early Pathé film La vie du Christ, which might be La Vie et la passion de Jésus-Christ (Lucien Nonguet, Ferdinand Zecca, 1903). Caption: The Entrance to Jerusalem. This image deviates from the one in the existing prints of Vie et passion de notre seigneur Jésus-Christ (Ferdinand Zecca, 1907).

![Le chat botté (1903)]()

French postcard by Croissant, Paris, mo. 3667. Photo: Pathé Frères. Scene from Le chat botté/Puss in Boots (Lucien Nonguet, 1903), based on the fairytale by Charles Perrault (1697). Actors: Bretteau and Edmond Boutillon. Caption: The King rescuing the Marquis of Carabas.

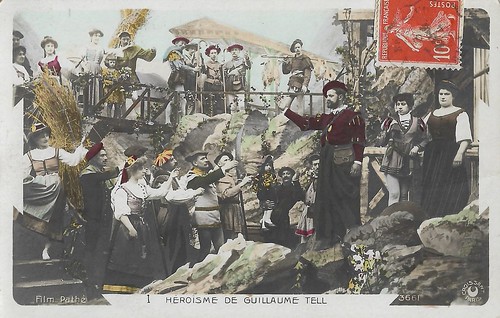

![Guillaume Tell. 1. Héroïsme de Guillaume Tell (1903)]()

French postcard by Croissant, Paris, series 3661. Photo: Film Pathé. Publicity still for Guillaume Tell (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) with Edmond Boutillon (Gessler). Sets: Vincent Lorant-Heilbronn. Théâtre Pathé Grolée, Lyon. It is unknown who played Tell. This exact image does not appear in the remaining print, as the acclamation at the end of the film takes place on a town square, while this setting refers to Tableau 1, near the river.

![Guillaume Tell, 2. Le serment de Grutli (1903)]()

French postcard by Croissant, Paris, series 3661. Photo: Film Pathé. Publicity still for Guillaume Tell (Lucien Nonguet, 1903). This card depicts the so-called Rütli-Schwur, the legendary oath taken at the foundation of the Old Swiss Confederacy.

![Guillaume Tell (Pathé, 1903)]()

Reproduction of Italian postcard by Ed. Alterocca, Terni, no. 3913, card 1 of 5. Photo: Cinématographes Pathé. Publicity still for Guillaume Tell/ William Tell (Lucien Nonguet, 1903). Caption: The boat has reached the other shore, Baumgarten is saved. (William Tell helps a peasant escape on a rowing boat just before a group of soldiers enters). This is the first film adaptation of the eponymous play by Friedrich Schiller and the opera by Rossini.

![Guillaume Tell (Pathé 1903)]()

Reproduction of Italian postcard by Ed. Alterocca, Terni, no. 3917. Photo: Cinématographes Pathé. Publicity still for Guillaume Tell/ William Tell (Lucien Nonguet, 1903). Caption: La mort de Gessler. La Suisse acclame Tell son libérateur. (The death of Gessler. Switzerland acclaims Tell as its liberator.)

Richard Abel, in his study 'The Cine Goes To Town. French Cinema, 1896-1914', indicates how by 1903 French films, in particular those by Pathé, created what would become "a standard mode of representation and narration for Pathé's longer films", that is: a series of long-shot tableaux with brief intertitles. This is clearly visible in two 1903 films by Pathé: Don Quichotte and Le chat botté/Puss-in-Boots. The first was composed of fifteen shot scenes, of which only half survives. Most shots focused on the farcical episodes of Cervantes' novel, Stencil colouring increased the spectacular effects of e.g. the explosion of the fake horse or the garish clothes of Sancho Panza when he is made governor. "What is especially unusual is its strategy of repeatedly representing two different spaces with the same tableau", such as the scene in which Don Quichotte and Sancho Panza attack a mill and nearly drown. Using a matte shot, we also see the people inside the mill at the same time. Pathé's Don Quichotte is also credited as being the first Pathé film with intertitles.

In Le chat botté/Puss-in-Boots (remade in 1908 by Albert Capellani), the same tableaux-style interspaced with brief intertitles was used. It may well have been based on stage pantomimes after the classic Charles Perrault tale. While the film has gruesome scenes similar to Méliès'films, such as the ogre throwing small children in a steaming cauldron, it also opens with a calm, Millet-like tableau of the miller's family. The penultimate tableau has a dance scene, an almost obligatory part of the early fairy tale films by Méliès and Pathé. The film ends with a typical apotheosis with angels on a staircase leading children to the top. While this version was entirely shot in a studio, Capellani would shoot several exteriors outside in woods or the French countryside, signalling a new shift in Pathé's fairy tale films.

By 1903, companies like Pathé started to shift from real or staged actualities to historical and realist films. After the success of George Méliès'The Coronation of Edward VII (1902), Pathé started making historical films, first Epopée napoléonienne (1903), "whose success securely established the single, unified view of the autonomous shot-scene as a characteristic feature of the genre." The two-part film strongly relied on French historical painting, thus creating a series of tableaux vivant-like scenes but then put into motion, citing the works by Vernet, David and Von Steuben. These paintings had already been popularised by stage tableau vivant of famous paintings, called 'realisations' at the time, as well as by school textbooks on history. Exhibitors were free to reduce or rearrange the series of tableaux of the film.

This flexibility was also typical for another Pathé film of 1903: La Vie et la Passion de Jésus-Christ, which followed earlier Life of Christ films by Lumière (1897), Gaumont (1899) and Pathé itself (1900). While American adaptations often were based on the Oberammergau passion play, Pathé composed its own script. The film was distributed in at least three different versions, of which the longest was almost 600 meters (ca. half an hour), which was unheard of in those years. It adhered to the tableau style, with each shot preceded by a short intertitle. Exhibitors were entirely free to buy whichever series or shots they wanted and could choose a black-and-white or a stencil-coloured version. While very little of this film remains and is not available online, several Passion films by Pathé put online erroneously claiming it to be 1903 while being instead the version of 1907 or 1913.

Epopée napoléonienne gave the go-ahead for a series of Pathé historical films in 1903-1904, including Guillaume Tell (1903). Inspired by the play by Friedrich Schiller (1804) and the opera by Gioacchino Rossini (1829), Lucien Nonguet and his art director Vincent Lorant-Heilbronn staged a film of 145 meters (about 7 to 8 minutes), which contained the most important moments of the story of the heroic Swiss liberator. Some elements were condensed. Within the Schiller tale, Tell first escapes from the boat with Gessler and his men, during a storm. Later on, he kills Gessler when the latter is riding in the woods near Küssnacht. In the Pathé film Tell jumps from the boat and kills Gessler right away.

![Napoléon à l'école de Brienne (1781)]()

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4434. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Napoléon à l'école de Brienne (1781).

![Bonaparte au pont d'Arcole (novembre 1796)]()

Italian postcard. Alterocca, Terni, no. 4435. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Bonaparte au pont d'Arcole (novembre 1796).

![Napoléon á les Pyramides (1798-99)]()

Italian postcard. Alterocca, Terni, no. 4436. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: apoléon á les Pyramides (1798-99).

![Passage du Mont St.-Bernard (mai 1800)]()

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4437. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Passage du Mont St.-Bernard (mai 1800).

![Une fête d'été à la Malmaison (1800)]()

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4438. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Une fête d'été à la Malmaison (1800).

![Le Couronnement de Bonaparte (1804)]()

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4440. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Le Couronnement de Bonaparte (1804).

![Napoléon à Austerlitz (2 déc. 1805)]()

Italian postcard. Alterocca, Terni, no. 4441. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Napoléon à Austerlitz (2 déc. 1805).

![Napoléon et la sentinelle endormie]()

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4442. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Napoléon et la sentinelle endormie.

![Les adieux de Fontainebleau (avril 1814)]()

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4443. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Les adieux de Fontainebleau (avril 1814).

![Waterloo (18 juin 1815)]()

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4444. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Waterloo (18 juin 1815).

Sources: Richard Abel (The Cine Goes To Town. French Cinema, 1896-1914), Henri Bousquet (Catalogue Pathé des années 1896-1914, Vol. I., 1896-1906 - French), Il Cinema Ritrovato, Fondation Jerome Seydoux Pathé, Wikipedia and IMDb.

In the same year, Pathé Frères ambitiously rivalled the grand féeries with spectacular productions by Lucien Nonguet about historical figures (Napoléon, Marie Antoinette). Several Pathé titles – part of the Corricks (itinerant showmen) collection – will be presented in restored versions originating from gorgeously hand-coloured prints found in Australia. For this post, Ivo Blom selected postcards of several Pathé films from 1903.

Don Quichotte

French postcard by Alterocca, Terni, Italy. Photo: Pathé Frères. Publicity still for Don Quichotte (Ferdinand Zecca, Lucien Nonguet, 1903). Sets were by Vincent Lorant-Heilbronn. Caption: Receiving the thanks of the liberated convicts. This scene lacks in the remaining print of the film. The 1903 version is the oldest film version of Cervantes' classic tale. It is unclear who the actors were. The writing on the card is in Slovenian and says: To the better healed at home, we extend our warmest regards to you.

Don Quichotte, fully titled Aventures de Don Quichotte de la Manche, was a film in 15 tableaux, measuring some 430 meters. A reduced version of 255 m. was also launched in 1903, possibly for exhibitors who thought a film of more than 15 minutes was too long for their audience. Pathé claimed in their catalogue that all the important scenes had been kept and the entire film had kept its original character.

La Vie et la Passion de Jésus-Christ

Franco-German postcard by PH, no. 6601. Photo: Film Pathé. This may be a scene from the 1903 film La Vie et la Passion de Jésus-Christ, started in 1902 by Ferdinand Zecca and finished in 1903 by Lucien Nonguet, when Zecca moved over to Gaumont. Caption: Vie de Christ, ep. 'Die Verkündigung' (the Annunciation).

French postcard. Photo: Pathé Frères. Scene from the early Pathé film La vie du Christ which might be La Vie et la passion de Jésus-Christ (Lucien Nonguet, Ferdinand Zecca, 1903). Caption: Jesus chases the merchants from the Temple. This image deviates from the one in the existing prints of Vie et passion de notre seigneur Jésus-Christ (Ferdinand Zecca, 1907).

French postcard. Photo: Pathé Frères. Scene from the early Pathé film La vie du Christ, which might be La Vie et la passion de Jésus-Christ (Lucien Nonguet, Ferdinand Zecca, 1903). Caption: The Entrance to Jerusalem. This image deviates from the one in the existing prints of Vie et passion de notre seigneur Jésus-Christ (Ferdinand Zecca, 1907).

Le chat botté

French postcard by Croissant, Paris, mo. 3667. Photo: Pathé Frères. Scene from Le chat botté/Puss in Boots (Lucien Nonguet, 1903), based on the fairytale by Charles Perrault (1697). Actors: Bretteau and Edmond Boutillon. Caption: The King rescuing the Marquis of Carabas.

Guillaume Tell

French postcard by Croissant, Paris, series 3661. Photo: Film Pathé. Publicity still for Guillaume Tell (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) with Edmond Boutillon (Gessler). Sets: Vincent Lorant-Heilbronn. Théâtre Pathé Grolée, Lyon. It is unknown who played Tell. This exact image does not appear in the remaining print, as the acclamation at the end of the film takes place on a town square, while this setting refers to Tableau 1, near the river.

French postcard by Croissant, Paris, series 3661. Photo: Film Pathé. Publicity still for Guillaume Tell (Lucien Nonguet, 1903). This card depicts the so-called Rütli-Schwur, the legendary oath taken at the foundation of the Old Swiss Confederacy.

Reproduction of Italian postcard by Ed. Alterocca, Terni, no. 3913, card 1 of 5. Photo: Cinématographes Pathé. Publicity still for Guillaume Tell/ William Tell (Lucien Nonguet, 1903). Caption: The boat has reached the other shore, Baumgarten is saved. (William Tell helps a peasant escape on a rowing boat just before a group of soldiers enters). This is the first film adaptation of the eponymous play by Friedrich Schiller and the opera by Rossini.

Reproduction of Italian postcard by Ed. Alterocca, Terni, no. 3917. Photo: Cinématographes Pathé. Publicity still for Guillaume Tell/ William Tell (Lucien Nonguet, 1903). Caption: La mort de Gessler. La Suisse acclame Tell son libérateur. (The death of Gessler. Switzerland acclaims Tell as its liberator.)

The ogre throwing small children in a steaming cauldron

Richard Abel, in his study 'The Cine Goes To Town. French Cinema, 1896-1914', indicates how by 1903 French films, in particular those by Pathé, created what would become "a standard mode of representation and narration for Pathé's longer films", that is: a series of long-shot tableaux with brief intertitles. This is clearly visible in two 1903 films by Pathé: Don Quichotte and Le chat botté/Puss-in-Boots. The first was composed of fifteen shot scenes, of which only half survives. Most shots focused on the farcical episodes of Cervantes' novel, Stencil colouring increased the spectacular effects of e.g. the explosion of the fake horse or the garish clothes of Sancho Panza when he is made governor. "What is especially unusual is its strategy of repeatedly representing two different spaces with the same tableau", such as the scene in which Don Quichotte and Sancho Panza attack a mill and nearly drown. Using a matte shot, we also see the people inside the mill at the same time. Pathé's Don Quichotte is also credited as being the first Pathé film with intertitles.

In Le chat botté/Puss-in-Boots (remade in 1908 by Albert Capellani), the same tableaux-style interspaced with brief intertitles was used. It may well have been based on stage pantomimes after the classic Charles Perrault tale. While the film has gruesome scenes similar to Méliès'films, such as the ogre throwing small children in a steaming cauldron, it also opens with a calm, Millet-like tableau of the miller's family. The penultimate tableau has a dance scene, an almost obligatory part of the early fairy tale films by Méliès and Pathé. The film ends with a typical apotheosis with angels on a staircase leading children to the top. While this version was entirely shot in a studio, Capellani would shoot several exteriors outside in woods or the French countryside, signalling a new shift in Pathé's fairy tale films.

By 1903, companies like Pathé started to shift from real or staged actualities to historical and realist films. After the success of George Méliès'The Coronation of Edward VII (1902), Pathé started making historical films, first Epopée napoléonienne (1903), "whose success securely established the single, unified view of the autonomous shot-scene as a characteristic feature of the genre." The two-part film strongly relied on French historical painting, thus creating a series of tableaux vivant-like scenes but then put into motion, citing the works by Vernet, David and Von Steuben. These paintings had already been popularised by stage tableau vivant of famous paintings, called 'realisations' at the time, as well as by school textbooks on history. Exhibitors were free to reduce or rearrange the series of tableaux of the film.

This flexibility was also typical for another Pathé film of 1903: La Vie et la Passion de Jésus-Christ, which followed earlier Life of Christ films by Lumière (1897), Gaumont (1899) and Pathé itself (1900). While American adaptations often were based on the Oberammergau passion play, Pathé composed its own script. The film was distributed in at least three different versions, of which the longest was almost 600 meters (ca. half an hour), which was unheard of in those years. It adhered to the tableau style, with each shot preceded by a short intertitle. Exhibitors were entirely free to buy whichever series or shots they wanted and could choose a black-and-white or a stencil-coloured version. While very little of this film remains and is not available online, several Passion films by Pathé put online erroneously claiming it to be 1903 while being instead the version of 1907 or 1913.

Epopée napoléonienne gave the go-ahead for a series of Pathé historical films in 1903-1904, including Guillaume Tell (1903). Inspired by the play by Friedrich Schiller (1804) and the opera by Gioacchino Rossini (1829), Lucien Nonguet and his art director Vincent Lorant-Heilbronn staged a film of 145 meters (about 7 to 8 minutes), which contained the most important moments of the story of the heroic Swiss liberator. Some elements were condensed. Within the Schiller tale, Tell first escapes from the boat with Gessler and his men, during a storm. Later on, he kills Gessler when the latter is riding in the woods near Küssnacht. In the Pathé film Tell jumps from the boat and kills Gessler right away.

L'Epopée napoléonienne

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4434. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Napoléon à l'école de Brienne (1781).

Italian postcard. Alterocca, Terni, no. 4435. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Bonaparte au pont d'Arcole (novembre 1796).

Italian postcard. Alterocca, Terni, no. 4436. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: apoléon á les Pyramides (1798-99).

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4437. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Passage du Mont St.-Bernard (mai 1800).

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4438. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Une fête d'été à la Malmaison (1800).

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4440. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Le Couronnement de Bonaparte (1804).

Italian postcard. Alterocca, Terni, no. 4441. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Napoléon à Austerlitz (2 déc. 1805).

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4442. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Napoléon et la sentinelle endormie.

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4443. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Les adieux de Fontainebleau (avril 1814).

Italian postcard by Alterocca, Terni, no. 4444. Photo: Cinématographe Pathé. Publicity still for L'Epopée napoléonienne (Lucien Nonguet, 1903) by Pathé Frères. Caption: Waterloo (18 juin 1815).

Sources: Richard Abel (The Cine Goes To Town. French Cinema, 1896-1914), Henri Bousquet (Catalogue Pathé des années 1896-1914, Vol. I., 1896-1906 - French), Il Cinema Ritrovato, Fondation Jerome Seydoux Pathé, Wikipedia and IMDb.