In our Summer series on recent film books, we have another Dutch subject. In 'Diva' Erik Brouwer tells the thrilling tale of the first and only Dutch actress with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Jetta Goudal (1891-1985) was an exotic and elegant beauty in silent American films in films by Cecil B. De Mille and other legendary directors. She was also an emancipated woman who had the guts to fight for her rights against the film bosses in court. How this ended and how it all began for Goudal in old Amsterdam, Brouwer tells in his well-written and exciting book (sorry, it's in Dutch) .

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Book cover for Erik Brouwer, 'Diva' (2018). Publisher: Uitgeverij Bern.

Jetta Goudal generally described herself as a ‘Parisienne’ and on an information sheet for the Paramount Public Department she later wrote that she was born at Versailles in 1901 as the daughter of Maurice Guillaume Goudal, a lawyer. Her publicist at one point even claimed that she was the daughter of legendary Dutch spy Mata Hari, but no one took that statement seriously, though.

Brouwer describes how she was born ten years earlier as Julie Henriette Goudeket, the daughter of Mozes Goudeket, a wealthy, orthodox Jewish diamond cutter in the Jordaan neighbourhood of Amsterdam.

Tall and regal in appearance, Julie began her acting career on stage, travelling across Europe with various theatre companies. In 1917, Julie Goudeket left a Europe, ravaged by World War I to settle in New York City.

There she hid her Dutch and Jewish ancestry and bluffed her way into Broadway. Goudal first appeared on the New York stage in the drama The Hero by Gilbert Emery in 1921, using the stage name Jetta (pronounced with a French J) Goudal. Later that year she returned with the melodrama The Elton Charm.

She met film director Sidney Olcott in a box at Carnegie Hall, who encouraged her to venture into film acting. She accepted a bit part in his film Timothy's Quest (Sidney Olcott, 1922) as a tubercular mother with children, in a pathetic scene with a drunken husband. Convinced to move to the West Coast, Goudal appeared in two more Olcott films in the ensuing three years.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

French postcard by Europe, no. 461. Photo: Regal Film / United Artists.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

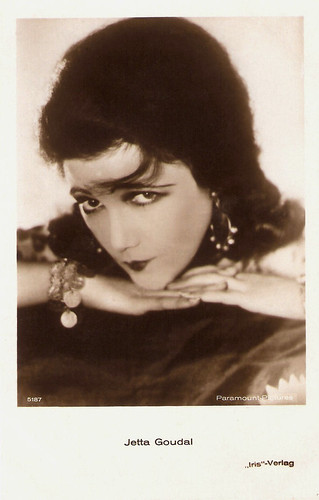

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 5187. Photo: Paramount.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 273.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

British postcard by Real Photograph.

Jetta Goudal's real film debut came in The Bright Shawl (John S. Robertson, 1923) with Richard Barthelmess. Jetta created quite a stir with her striking, exotic appearance in a secondary role as a Chinese/Peruvian spy. Critics found her "different" and "distinctive."

She quickly earned more praise for her following film work, especially for her performance in Salome of the Tenements (Sidney Olcott, 1925), a film based on the Anzia Yezierska novel about life in New York's Jewish Lower East Side. Goudal then worked in the Adolph Zukor and Jesse L. Lasky co-production of The Spaniard (Raoul Walsh, 1925) opposite Ricardo Cortez– ‘the new Sheik’- in his first starring role.

In a documentary by Do Groen at the book's website, film historian Sam Gill explains that film makers chose her because she had an unusual way of gesturing and of talking. Film researcher Joseph Ytansky adds: "She glimmers when you see her on screen. She's absolutely radiant. She has this glowing complexion and that wonderfully slightly evil smile. She's absolutely fantastic."

Her growing fame brought her to the attention of producer/director Cecil B. DeMille. He hired her for what turned out to be some of her (and his) greatest critical successes, including her emotional roles in the highly romantic melodrama The Coming of Amos (Paul Sloane, 1925) starring Rod LaRocque, The Road to Yesterday (Cecil B. DeMille, 1925), the excellent mystery melodrama Three Faces East (Rupert Julian, 1926), the extremely powerful drama White Gold (William K. Howard, 1927) and the lush desert romantic melodrama The Forbidden Woman (Paul L. Stein, 1927) with Victor Varconi.

Jetta had strong convictions about everything in life. She spoke her mind and could be difficult. If she thought something in a film was not real and belonged to the character, she did not want to play it. Reportedly, the famous costume designer Adrian passed out after a costume fitting with her. He collapsed on the floor and people had to help him. Cecil DeMille liked Jetta at first and thought she was a very good actress. Later he claimed that Goudal was so difficult to work with that he eventually fired her and cancelled their contract.

Goudal felt disrespected. It hurt her deeply that she was called unprofessional and Jetta filed a lawsuit for breach of contract against the man who was called 'God' in Hollywood and his DeMille Pictures Corporation. The powerful DeMille claimed her conduct had caused numerous and costly production delays, but in a landmark ruling Goudal won the suit when DeMille was unwilling to provide his studio's financial records to support his claim of financial losses.

Erik Brouwer describes Jetta's long battle against the man, everybody in Hollywood was afraid of. Until her death Goudal was justifiably proud of her victory, it was a milestone. Partly as a result of her efforts Equity was set up. The actors' union would give actors and actresses more legal rights from then on. They would not have to obey any longer to every order issued by producers like De Mille.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Jetta Goudal]()

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1475/1, 1927-1928. Photo: DPC.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Jetta Goudal]()

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3332/1, 1928-1929. Photo: DPC.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Jetta Goudal]()

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3332/2, 1928-1929. Photo: LPG.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Jetta Goudal]()

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3947/1, 1928-1929. Photo: United Artists.

Jetta Goudal's career was not over after she sued De Mille. She appeared as a vamp opposite Marion Daviesand Nils Asther in The Cardboard Lover (Robert Z. Leonard, 1928), produced by William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies.

In 1929, she starred with Lupe Velez and cowboy star William Boyd in Lady of the Pavements (D.W. Griffith, 1929), a romantic drama set in the time of Napoleon in Paris. At IMDb, reviewer Drednm loves it: "While William Boyd hasn't much to do here as the Count, the two leading ladies tear the place apart. Fiery Lupe Velez is superb as Nanon, taking full advantage of the comic scenes but then turning in a terrific dramatic performance in the finale. Jetta Goudal is gorgeous and lethal as Diane, using her haughty beauty to good effect."

The next year Jacques Feyder directed Goudal in her only French language film, Le Spectre vert/The Green Spectre (Jacques Feyder, 1930), a made-in-Hollywood, alternate language version of The Unholy Night (1929).

Because of her audaciousness in suing DeMille and her high-profile activism in the Actors Equity's fight for the unionisation of film actors she became known as 'the Joan of Arc of Equity'. Some of the Hollywood studios refused to employ 'the Bolshewist of the Movie Industry' and with the arrival of sound her thick accent left her with limited offers.

At age forty-one, she made her last screen appearance in a talkie, the comedy Business and Pleasure (David Butler, 1932), co-starring with Will Rogers. In 1930, she had married Harold Grieve, an art director and founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Along with her husband, she went into interior design and faded from the Hollywood scene. They had no children.

Plagued by health problems (heart condition) in the 1960s, she suffered a serious fall in 1973 which left her virtually an invalid. She told an interviewer in 1985: "I don't like being called a silent star. Who was silent? I was never silent!" Shortly after, Jetta Goudal died in 1985 in Los Angeles, at age 94.

Erik Brouwer makes clear what a complicated person Jetta Goudal was. She was a perfectionist, which hounded her. She had her demons. About De Mille she said that she trusted him like a father. She was so upset by his actions that she was in a hospital for a year. She never wrote to her real conservative Jewish father, not even after her mother had died in 1921.

The title of the book is well chosen. Jetta Goudal was a diva. She would often throw fits and just walk off. But she was also a kind person. Film historian Anthony Slide explains in the documentary that "difficulty was part of her make-up." She demanded perfection like she wanted perfection in the things around her. Playing the role of being Jetta Goudal must have been difficult. But, as a friend says: "It was something magnificent to be."

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Jetta Goudal]()

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3791/1, 1928-1929. Photo: MGM (Metro Goldwyn Mayer).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Jetta Goudal]()

French postcard.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Jetta Goudal]()

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Édition, Paris, no. 511.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Jetta Goudal]()

French postcard, no. 37. Photo: Erka-Prodisco. Erka-Prodisco Films was a French film distribution company. Her name is erroneously written as Jetta Gondal.

Sources: Erik Brouwer (Diva - Dutch), Charles C. Benham (Classic Images), Hans J. Wollstein (AllMovie), Operator_99 (Allure), Gary Brumburgh (IMDb), Wikipedia, and IMDb.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Book cover for Erik Brouwer, 'Diva' (2018). Publisher: Uitgeverij Bern.

A Parisienne from Amsterdam

Jetta Goudal generally described herself as a ‘Parisienne’ and on an information sheet for the Paramount Public Department she later wrote that she was born at Versailles in 1901 as the daughter of Maurice Guillaume Goudal, a lawyer. Her publicist at one point even claimed that she was the daughter of legendary Dutch spy Mata Hari, but no one took that statement seriously, though.

Brouwer describes how she was born ten years earlier as Julie Henriette Goudeket, the daughter of Mozes Goudeket, a wealthy, orthodox Jewish diamond cutter in the Jordaan neighbourhood of Amsterdam.

Tall and regal in appearance, Julie began her acting career on stage, travelling across Europe with various theatre companies. In 1917, Julie Goudeket left a Europe, ravaged by World War I to settle in New York City.

There she hid her Dutch and Jewish ancestry and bluffed her way into Broadway. Goudal first appeared on the New York stage in the drama The Hero by Gilbert Emery in 1921, using the stage name Jetta (pronounced with a French J) Goudal. Later that year she returned with the melodrama The Elton Charm.

She met film director Sidney Olcott in a box at Carnegie Hall, who encouraged her to venture into film acting. She accepted a bit part in his film Timothy's Quest (Sidney Olcott, 1922) as a tubercular mother with children, in a pathetic scene with a drunken husband. Convinced to move to the West Coast, Goudal appeared in two more Olcott films in the ensuing three years.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

French postcard by Europe, no. 461. Photo: Regal Film / United Artists.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Austrian postcard by Iris-Verlag, no. 5187. Photo: Paramount.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

British postcard in the Picturegoer Series, London, no. 273.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

British postcard by Real Photograph.

Different and Distinctive

Jetta Goudal's real film debut came in The Bright Shawl (John S. Robertson, 1923) with Richard Barthelmess. Jetta created quite a stir with her striking, exotic appearance in a secondary role as a Chinese/Peruvian spy. Critics found her "different" and "distinctive."

She quickly earned more praise for her following film work, especially for her performance in Salome of the Tenements (Sidney Olcott, 1925), a film based on the Anzia Yezierska novel about life in New York's Jewish Lower East Side. Goudal then worked in the Adolph Zukor and Jesse L. Lasky co-production of The Spaniard (Raoul Walsh, 1925) opposite Ricardo Cortez– ‘the new Sheik’- in his first starring role.

In a documentary by Do Groen at the book's website, film historian Sam Gill explains that film makers chose her because she had an unusual way of gesturing and of talking. Film researcher Joseph Ytansky adds: "She glimmers when you see her on screen. She's absolutely radiant. She has this glowing complexion and that wonderfully slightly evil smile. She's absolutely fantastic."

Her growing fame brought her to the attention of producer/director Cecil B. DeMille. He hired her for what turned out to be some of her (and his) greatest critical successes, including her emotional roles in the highly romantic melodrama The Coming of Amos (Paul Sloane, 1925) starring Rod LaRocque, The Road to Yesterday (Cecil B. DeMille, 1925), the excellent mystery melodrama Three Faces East (Rupert Julian, 1926), the extremely powerful drama White Gold (William K. Howard, 1927) and the lush desert romantic melodrama The Forbidden Woman (Paul L. Stein, 1927) with Victor Varconi.

Jetta had strong convictions about everything in life. She spoke her mind and could be difficult. If she thought something in a film was not real and belonged to the character, she did not want to play it. Reportedly, the famous costume designer Adrian passed out after a costume fitting with her. He collapsed on the floor and people had to help him. Cecil DeMille liked Jetta at first and thought she was a very good actress. Later he claimed that Goudal was so difficult to work with that he eventually fired her and cancelled their contract.

Goudal felt disrespected. It hurt her deeply that she was called unprofessional and Jetta filed a lawsuit for breach of contract against the man who was called 'God' in Hollywood and his DeMille Pictures Corporation. The powerful DeMille claimed her conduct had caused numerous and costly production delays, but in a landmark ruling Goudal won the suit when DeMille was unwilling to provide his studio's financial records to support his claim of financial losses.

Erik Brouwer describes Jetta's long battle against the man, everybody in Hollywood was afraid of. Until her death Goudal was justifiably proud of her victory, it was a milestone. Partly as a result of her efforts Equity was set up. The actors' union would give actors and actresses more legal rights from then on. They would not have to obey any longer to every order issued by producers like De Mille.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 1475/1, 1927-1928. Photo: DPC.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3332/1, 1928-1929. Photo: DPC.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3332/2, 1928-1929. Photo: LPG.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3947/1, 1928-1929. Photo: United Artists.

Vamp or Joan of Arc?

Jetta Goudal's career was not over after she sued De Mille. She appeared as a vamp opposite Marion Daviesand Nils Asther in The Cardboard Lover (Robert Z. Leonard, 1928), produced by William Randolph Hearst and Marion Davies.

In 1929, she starred with Lupe Velez and cowboy star William Boyd in Lady of the Pavements (D.W. Griffith, 1929), a romantic drama set in the time of Napoleon in Paris. At IMDb, reviewer Drednm loves it: "While William Boyd hasn't much to do here as the Count, the two leading ladies tear the place apart. Fiery Lupe Velez is superb as Nanon, taking full advantage of the comic scenes but then turning in a terrific dramatic performance in the finale. Jetta Goudal is gorgeous and lethal as Diane, using her haughty beauty to good effect."

The next year Jacques Feyder directed Goudal in her only French language film, Le Spectre vert/The Green Spectre (Jacques Feyder, 1930), a made-in-Hollywood, alternate language version of The Unholy Night (1929).

Because of her audaciousness in suing DeMille and her high-profile activism in the Actors Equity's fight for the unionisation of film actors she became known as 'the Joan of Arc of Equity'. Some of the Hollywood studios refused to employ 'the Bolshewist of the Movie Industry' and with the arrival of sound her thick accent left her with limited offers.

At age forty-one, she made her last screen appearance in a talkie, the comedy Business and Pleasure (David Butler, 1932), co-starring with Will Rogers. In 1930, she had married Harold Grieve, an art director and founding member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Along with her husband, she went into interior design and faded from the Hollywood scene. They had no children.

Plagued by health problems (heart condition) in the 1960s, she suffered a serious fall in 1973 which left her virtually an invalid. She told an interviewer in 1985: "I don't like being called a silent star. Who was silent? I was never silent!" Shortly after, Jetta Goudal died in 1985 in Los Angeles, at age 94.

Erik Brouwer makes clear what a complicated person Jetta Goudal was. She was a perfectionist, which hounded her. She had her demons. About De Mille she said that she trusted him like a father. She was so upset by his actions that she was in a hospital for a year. She never wrote to her real conservative Jewish father, not even after her mother had died in 1921.

The title of the book is well chosen. Jetta Goudal was a diva. She would often throw fits and just walk off. But she was also a kind person. Film historian Anthony Slide explains in the documentary that "difficulty was part of her make-up." She demanded perfection like she wanted perfection in the things around her. Playing the role of being Jetta Goudal must have been difficult. But, as a friend says: "It was something magnificent to be."

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

German postcard by Ross Verlag, no. 3791/1, 1928-1929. Photo: MGM (Metro Goldwyn Mayer).

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

French postcard.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

French postcard by Cinémagazine-Édition, Paris, no. 511.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

French postcard, no. 37. Photo: Erka-Prodisco. Erka-Prodisco Films was a French film distribution company. Her name is erroneously written as Jetta Gondal.

Sources: Erik Brouwer (Diva - Dutch), Charles C. Benham (Classic Images), Hans J. Wollstein (AllMovie), Operator_99 (Allure), Gary Brumburgh (IMDb), Wikipedia, and IMDb.